Antifragility (part 1)

Hey all -

You know that feeling when you’re studying something new, and nothing makes sense, until you finally reach an epiphany - a new plateau in understanding - that ties everything together? Before, you had a bunch of disjointed facts and concepts and theory, but now there is some overarching framework that ties everything together. There is a higher-order mental model that coherently organizes the concepts below.

For me, antifragility - a term coined by the writer Nassim Taleb - is one of those higher-order mental models. Antifragility offers a new perspective for understanding things like resilience engineering, optimization, nonlinearity, adaptability, and Knightian uncertainty. It’s one of the mental models which has most impacted the way I think.

Antifragility was the subject of Taleb’s 2014 book Antifragile - and since this is a newsletter, not a book, there’s no way I can do justice to the entire concept. But I hope to introduce some of the main ideas below.

+ what I learned or rediscovered recently #

Antifragility #

As I’ve written before, humans really don’t like uncertainty. The unknown is threatening. It makes us physically and psychologically uncomfortable. Wherever possible, we try to reduce this uncertainty.

In fact, you could argue that our whole purpose in life is to transform uncertainty, the unknown, the unpredictable - even if it’s at the edge of the universe - into something we can understand, predict and control.

Don’t know when your next meal will be? Rely on agriculture. Don’t know when it will rain? Use irrigation. Don’t know when a disease will wipe out your crop? Apply pesticide. Everything we do in life is an attempt to make the world a little bit more orderly.

Mankind has been remarkably successful at controlling the natural world. But success has also brought overconfidence. Not only can we eradicate uncertainty, we ought to. We measure, plan, theorize and of course - predict - in order to control the real world.

The problem is that we are never able to fully control the natural world. There will always be outlier events - both positive and negative - which catch us off guard. We will be surprised eventually - so how do we prepare for the things we inherently can’t prepare for?

Taleb argues that there are three types of systems - fragile, robust, and antifragile – which govern how we respond to these external, and sometimes extreme, shocks. (I’ll skip robust because it’s not particularly relevant.)

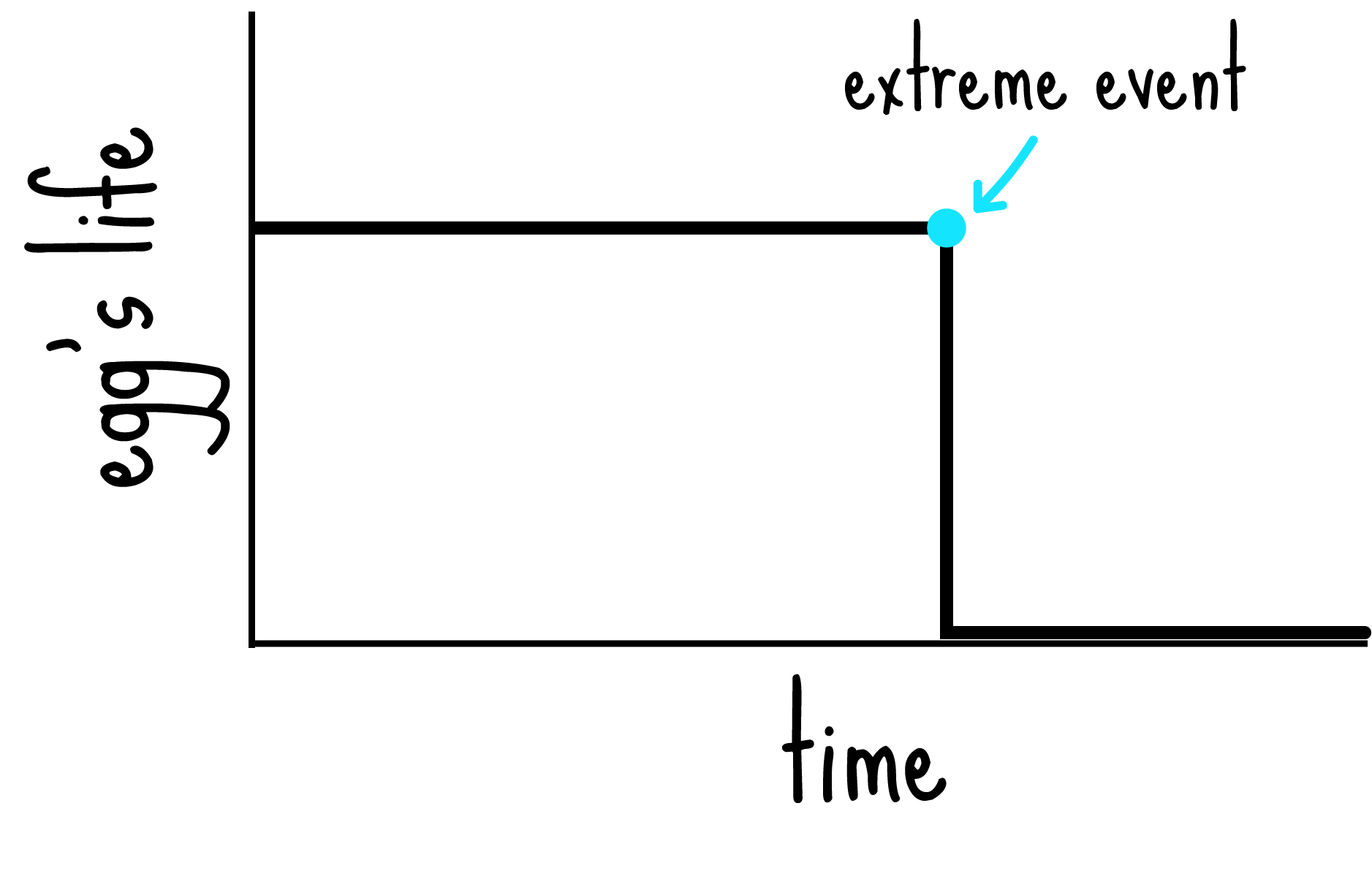

A fragile system is one that is especially exposed on the downside to disorder. A classic example of fragility is an egg: it’s fine if you do nothing to it, but if you drop it, it will crack open. If you graphed the life of the egg, it’d look something like this:

There’s a fundamental asymmetry here: the downside - even if improbable - far outweighs the upside. This asymmetry defines the system. Things go well - until they go horribly wrong. Obviously, we don’t want to be fragile.

Surprisingly, there are systems that gain from disorder, and these are the systems that Taleb is particularly interested in. These systems improve when they confront stress, shocks and uncertainty. For example, when you exercise at the gym, you damage your body so that it can self-repair. When you face your fears - maybe it’s public speaking or speaking your mind - you become more confident. By inducing stress, antifragile systems grow stronger.

Unlike eggs, humans are antifragile systems[1]. When we are challenged - be it physically or mentally - we change, adapt, and grow. When we are not challenged, we atrophy. In order to improve, we need to shock the system.

This produces a counterintuitive conclusion: far from extinguishing randomness from our lives, we should encourage it. It’s painful, uncomfortable and unpleasant - but it’s how antifragile systems grow stronger.

If we eliminate stress and unpredictability from our lives, we will be unprepared for when extreme events inevitably do occur. We become fragile.

Antifragility teaches us other things too. It teaches us how we should think about optimization and heuristics and patience and nonlinearity, all of which I hope to tease out in the next newsletter. In the meantime, here’s a great post by USV’s Albert Wenger that outlines the main arguments of antifragility.

Thanks for reading,

Alex

[1] Unlike eggs, humans are also complex adaptive systems. Adaptation is a critical feature of antifragility.