What makes a leader versus just a manager?

Over the years and at a handful of different companies, I’ve come to recognize what I call “organizational pathologies”. These are ways in which organizations, in theory designed to work toward a common goal, instead internally fray into myriad directions and in ultimately self-destructive ways.

I’ve been on projects lacking a cohesive vision, causing team members to work haphazardly on their tasks without a clear sense of what’s next or why. I’ve witnessed teams encouraged to work together which have no desire to work together, leading to stubbornly persistent information silos despite weekly “knowledge sharing” meetings. And I’ve seen projects, without a compelling raison d’être, lose their initial momentum and instead succumb to the slow death of organizational irrelevance.

No matter the cause, the effect is the same: lost time, lost energy and lost morale.

What do these pathologies have in common? One might argue it was mismanagement, or perhaps miscommunication or misalignment, but I would argue the cause was deeper. They all stem from an absence of strong leadership.

What does it mean to lead? #

As someone quick to extol the virtues of hard, technical, engineering skills, I can sometimes be reluctant to appreciate the softer skills of “leadership” or “management”. Engineers pride themselves in what they build. Leaders pride themselves in what they say.

Nevertheless, the longer I’ve spent in large organizations, the more I’ve come to realize that what is publicly spoken is very important.

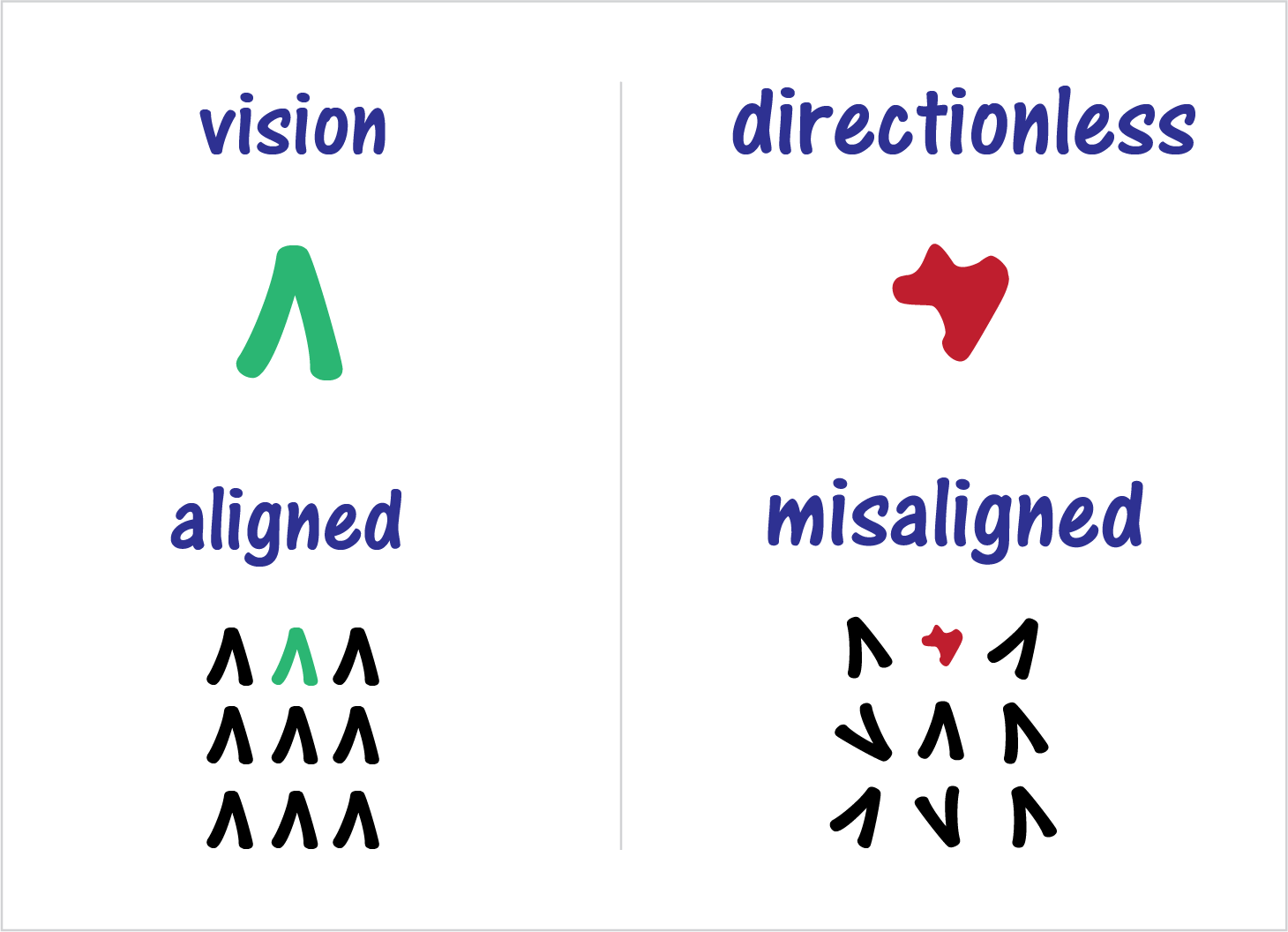

Leaders, be they technical leaders or sales leaders or operational leaders, produce two key outcomes for an organization:

- They provide a vision. “We should do this”

- They secure alignment. “We all agree we should do this”

Leadership, as I define it, is not about doing. Managers, whose job it is to deliver results, are responsible for doing. Leaders define and broadcast what ought to be done.

One can be a consummate operator (the COO skillset) but be entirely uninspiring when it comes to setting a vision. Conversely one can be a powerful visionary (the CEO skill set) but be remarkably incompetent at delivering on such promises. Naturally, the best leaders combine both skill sets: the ability to lead and the ability to deliver.

Leaders operate within the plane of ideas. They advance their vision of how the future should look, then negotiate this vision with other stakeholders (e.g. peers, subordinates, managers, the general public). What results is a broader, more consensual and ultimately more synoptic organizational vision.

While managers talk in the present about “what we are working on”, leaders talk in the future about “what we should be working on.” Managers focus on operations and execution; leaders on strategy and vision. Both are invaluable ingredients to uniting a large group of people and making progress toward a common goal.

The output of leaders materializes as mission statements, corporate values, culture decks, project roadmaps, investment theses and elevator pitches. They look like Bridgewater’s cultural principles, Amazon’s leadership principles, Stripe’s operating principles. Leaders are consumed by “culture” because they operate in the realm of ideas, ideas which are installed from day one on every team member’s operating system.

When decoupled from capable execution, such ideas reflect the hollow proclamations of distant and disconnected leadership. When coupled with capable execution, they represent the highest standards of decision-making to which all team members can aspire.

What makes a compelling vision? #

Teams need to feel like they are making progress over time toward some common goal. This goal should be:

- Stable over time: it does not change day-to-day or week-to-week

- Superordinate: it encompasses smaller goals in service of the larger goal

- Logical: it is not unrealistic, self-contradictory or evidently false

- Concise: it can be communicated in just a few sentences, rather than in a few pages

- Inspirational: it should appeal to a fundamental human need (e.g. to make a difference, to improve oneself or the world)

The canonical example of a compelling vision is “operational excellence.” It is stable year-to-year, accommodating of smaller projects (as long as they all exemplify operational excellence), immediately comprehensible, and challenging but also achievable. Due to its concision, it is straightforward to evaluate any deliverable and state “this reflects operational excellence” or “this does not”.

Of course, no vision is perfect (how can it be when reduced to two words?), but it must be good enough for people to believe in. If people do not believe in your vision, they certainly will not build it.

What is the litmus test of a compelling vision? It is one that gets other people to follow it.

How to secure buy-in for your vision #

Although a compelling vision is necessary to have other people follow it, it is not sufficient. That is because when they are evaluating your vision, they are also evaluating you. If they don’t like you or don’t trust you, for example, they will dismiss whatever you have to say before you even say it.

People will typically evaluate you along two primary axes[0]:

- Warmth: Can I trust that you have my best interests in mind?

- Competence: Can I trust that you will deliver on your promises?

First, what do people want? There is of course considerable psychological literature on this topic, but one might surmise that most people are generally motivated by roughly the same things[1]:

- Autonomy: the ability to make one’s own choices and pursue one’s own interests

- Mastery: the ability to develop new skills and use those skills toward achieving one’s goals

- Purpose: the feeling of making difference and working on something important

- Recognition: the feeling of being needed, being important, and being rewarded commensurately

- Relatedness: the feeling of being on the same team or tribe as others

Second, why should people believe that you will deliver on these? Because ideally you are credible. You have:

- Reputational capital: you will deliver in the future because you have delivered in the past

- Group membership: you will deliver because you’re “one of us” (and if I could deliver, so could you)

- Social proof: you will deliver because other people say you will deliver

Here we see that good leaders often need to be good managers. They must not only “talk the talk” but also “walk the walk”. If you have a reputation for not delivering on what you say you will do, you will be - in the words of one of my friends - “politically bankrupt.” Similarly, if you are unrelatable and make no effort to be relatable, you will be less trusted. And finally, if other people think you are wrong (and worse, publicly state it), it will be very difficult to convince others you are right.

Good leaders build reputational capital over time, aim to be relatable and secure buy-in from their closest allies in order to give team members what they want. In return, they earn buy-in into their vision.

Produce the first draft, not the only draft #

I like to say that good leaders should shop around their ideas early and often. As a leader and strategist, they produce ideas, but as a negotiator and tactician, they understand their ideas must be owned and enhanced by the people they work with.

The simplest maxim I follow to achieve this is “produce the first draft, not the only draft.”

Leaders should be the first to suggest better ways of doing things. I am always struck by how infrequently people identify and act on better ways of doing things; far more often, people follow what has always been done (typically elsewhere, on the Internet, with little reflection on whether it’d work here). Leaders must produce this first draft, often quite literally on a piece of paper, such as a values statement, project plan or technical specification.

But that is just the first draft. Inevitably, it is at times incomplete, incomprehensible and perhaps illogical. Even from the best thinkers, this is to be expected. Accordingly, leaders must shop around their ideas. This achieves two goals: it stress tests their ideas (which almost certainly have omissions and inconsistencies), and it gets others to share ownership in the vision (which consequently earns their buy-in). That is why leaders must get others to produce their own ideas and contribute to the shared vision - that is, the “final draft”.

You may notice that most of what I described as leadership seems rather political. Indeed, any collaborative human activity is inherently political. The moment you need to unite a large group of people (who invariably have their own interests at heart) toward a common goal, you will enter the realm of politics. This is not to say that politics is a bad thing or a good thing; it simply is a thing, and one that has been around for a very, very long time.

Like good software, politics done well is politics you don’t even notice. Politics done poorly, on the other hand, manifests as “office politics” and “poor leadership”. Good leaders make politics invisible.

Generally speaking, more people should aim to cultivate leadership traits. It does not belong exclusively to the skill set of CEOs; rather, it is required for anyone who manages others or coordinates anything across many people.

--

[0] Based on the stereotype content model in social psychology.

[1] The first three are from Daniel Pink’s Drive, the second-to-last comes from Jason Cohen’s “[joy-skill-need]” framework, and the last comes from self-determination theory.