Hanlon's razor, coalition building

Hey all -

+ what I learned or rediscovered recently #

Hanlon’s razor #

From time to time, people behave in such a way that makes us think: What a jerk.

Now the thing about being a jerk is it implies some degree of intent. Jerks often act in conveniently self-serving ways, such as being chronically late to meetings, or “forgetting” to do their dishes. Another driver may swerve in front of you to avoid an accident, but only a jerk would swerve in front of you to get home a bit faster.

Incredibly, only other people can be jerks. Hmmm - so there’s our first hint of bias.

Surely we don’t intend to be jerks, therefore we can’t possibly be jerks. But maybe other people don’t intend to be jerks either? Maybe, like us, they are simply unaware of the degree to which their actions are harming others?

We could say this is the “charitable interpretation”: rather than intending to be jerks, people don’t know any better. Alas, this is Hanlon’s razor:

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

Why is this a better reaction?

Well if someone is acting with malice, the situation is virtually unresolvable. Do we remain passive-aggressive and plot our revenge (the most common tactic)? Do we escalate and yell back? Tensions only rise here.

But if we first allow for the possibility that someone simply doesn’t know any better, that’s actually quite resolvable. Ironically, the burden to resolve the problem is on us - not them. We need to explain and communicate the problem. If only they saw the consequences of their actions, they’d probably behave differently. This is a much more cooperative approach.

Of course, sometimes people are jerks - and there’s nothing more to it. But by trying to explain the problem first by ignorance instead of malice, the responsibility now lies squarely upon us to communicate and cooperate more effectively.

Coalition building #

This is a term that’s most often used in politics, particularly when referring to politicians or organizations securing buy-in from other groups in order to achieve common goals.

“Coalition building” initially strikes me as so vague as to be almost meaningless. Aren’t we always securing buy-in from others around our ideas and goals - whether it’s planning an event or deciding where to go for dinner? Does it suddenly become “coalition building” when it occurs within politics, or when it concerns grandiose goals? Most importantly, can it be abstracted out of politics? I think so.

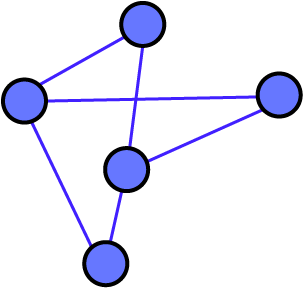

In my mind, coalition building is better understood in graphs. We start with a little network like this:

This network - be it a company or an organization or a group of friends - is working together to achieve something. Or maybe they just have a shared ethos which ties them together.

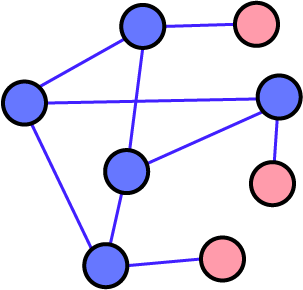

And if they want to grow their network, step-by-step, they could recruit new nodes onto the network like this:

And over time they’d build a larger, more influential group. But this is slow - you have to recruit each node individually into the network.

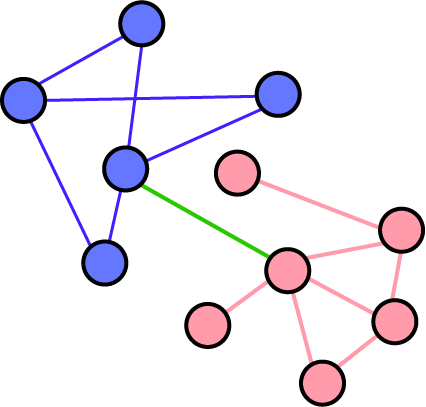

Another approach you could take is to target someone or some organization of influence and recruit them to the network - and then their network would follow.

This seems like a much more efficient way of building the network[1]. You only have to get a few central nodes, instead of all the little players.

So while coalition building is really relationship building, it’s a particular kind of relationship building. It’s not like networking, where you go for just anyone. Coalition building implies going for the big, most influential players - and if you get them, you get their whole network. Coalition building then is not simply about expanding your reach; it’s about the strategic steps necessary to make sure you’re going for the central nodes.

+ here’s something I wrote #

Orthogonal iteration #

I wrote an essay here on what I call “orthogonal iteration.” Namely, what if every time we wanted to improve something - say our workouts or relationships or work habits - we didn’t simply incrementally change what we were already doing, but rather, radically switched gears?

For example, let’s say we’re trying to improve the time in which we run a mile. We could practice running a mile everyday and incrementally improve our progress. Or, we could try something radically different: change our diet, practice sprints, start lifting weights, and so on.

It’s not clear whether any of these will actually increase our running performance - and, there is always a cost to search - but we may find performance boosts which operate on a completely different axis. In essence, by exploring a broader opportunity space, we are “unlocking” potential performance gains that are otherwise unreachable.

Now, there are tradeoffs to everything - namely, we don’t want to quit what already works. But I do wonder to what extent we’d benefit from iterating orthogonally instead of incrementally.

Thanks for reading,

Alex

[1] Tradeoffs here too, of course, such as the network becoming too diffuse or the network becoming highly centralized.