To be persuasive, you need more than logic

As someone who likes to think they’re fairly rational, I’ve always been suspicious of emotions. They’re fickle, they’re inconsistent and they’re easily to manipulate. Salespeople are well-aware of this, so I’ve been doubly suspicious of salespeople my whole life.

As a result, when anyone tries to convince me through patently emotional messaging - for example, appealing to my short-term desires or impulses - I immediately shut them out. I need to see some appeal to reason, some appeal to facts - not because I will always understand the facts - but because this style of persuasion signals who I am dealing with.

Overall, I think it’s a useful heuristic - but, like all heuristics, it’s imperfect.

As I reflected more on this idea though - the idea that I need to identify rationality to be convinced of anything - I’m not so convinced of its merit anymore.

The reason we do anything is because of emotions. It’s the first brain we have - the limbic system - and it’s the first brain we must satisfy. Only after does the prefrontal cortex kick in for any kind of decision-making. The rational part comes second. Daniel Kahneman calls these System 1 and System 2, respectively, but more colloquially they’re called the lizard brain and the monkey brain.

This doesn’t mean that we should ignore the facts. But it does tell us that any message devoid of emotional content will be absolutely ineffective in changing our behavior. It’s not what our brains evolved for. If we want to change our behavior, for better or for worse, we need to satisfy that first brain.

Let me give you an example. If I tell you “22 people died in Cambodia” - there’s a lot of conceptual scaffolding there. Our brains did not evolve for numbers, such as “22”. On top of that, you have people - but I don’t know a “people.” I know my friends and family - their faces, their behavior, their idiosyncrasies. Even “Cambodia” is a remote concept, especially so if I’ve never been there. This is why news that happens on the other side of the world always seems so irrelevant: to our brains, it’s just a concept.

To put it concisely, concepts do not convince. Emotions do. Stringing together facts and figures and numbers will simply not be effective in changing human behavior.

Again, this doesn’t mean we should ignore the facts. Ultimately, to successfully operate in this world, we must interface with an objective, coherent, underlying reality. Facts, concepts, and logical reasoning help us do that - they must have some fidelity to the real world. The truth matters.

But if we want to convince others of the truth, we cannot do that using concepts alone. Concepts are not part of the prehistoric brain’s vocabulary - only emotions are. And ultimately, we need to convince others if we want to cooperate and achieve things at scale - a hallmark of modern civilization.

This is an unfortunate paradox: we require concepts to understand the real world, but our brains are wholly unequipped to communicate in those terms. How do we resolve this?

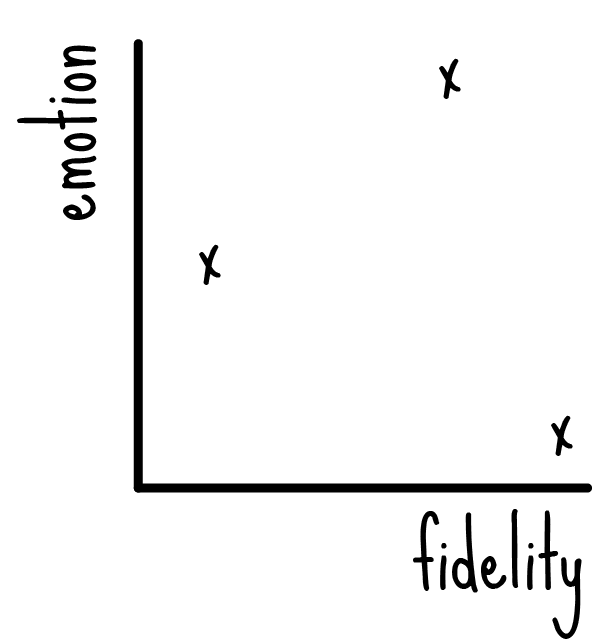

We should evaluate messages along two axes. The first is fidelity: are the cause-and-effect statements, the relationships between entities, the magnitude of things - are they actually true? If not, we will be thwarted by the constraints imposed by the real world.

The second is emotional content: even if we identify the way the world truly works, we can’t do anything about it unless we convince others to cooperate with us. The language we must use here is not one of theory and concepts, but of emotions.

To think - as I thought - that any appeal to emotions is manipulative…that’s naive. It’s the system we have to work with given the wetware inside our heads. It’s our default mode of understanding. Facts let us see the world for what it is, but to communicate it, we must rely - in part at least - on emotions.