The left and the right hands of data #

On my team at work, I seem to talk endlessly about the importance of “data correctness”1.

We data practitioners typically focus on building things. We write code, model data, build dashboards, formulate regressions, and develop machine learning models. We are happy when code compiles and unhappy when it doesn’t.

When everything works, we move on. There’s always the next data set, the next dashboard, the next model.

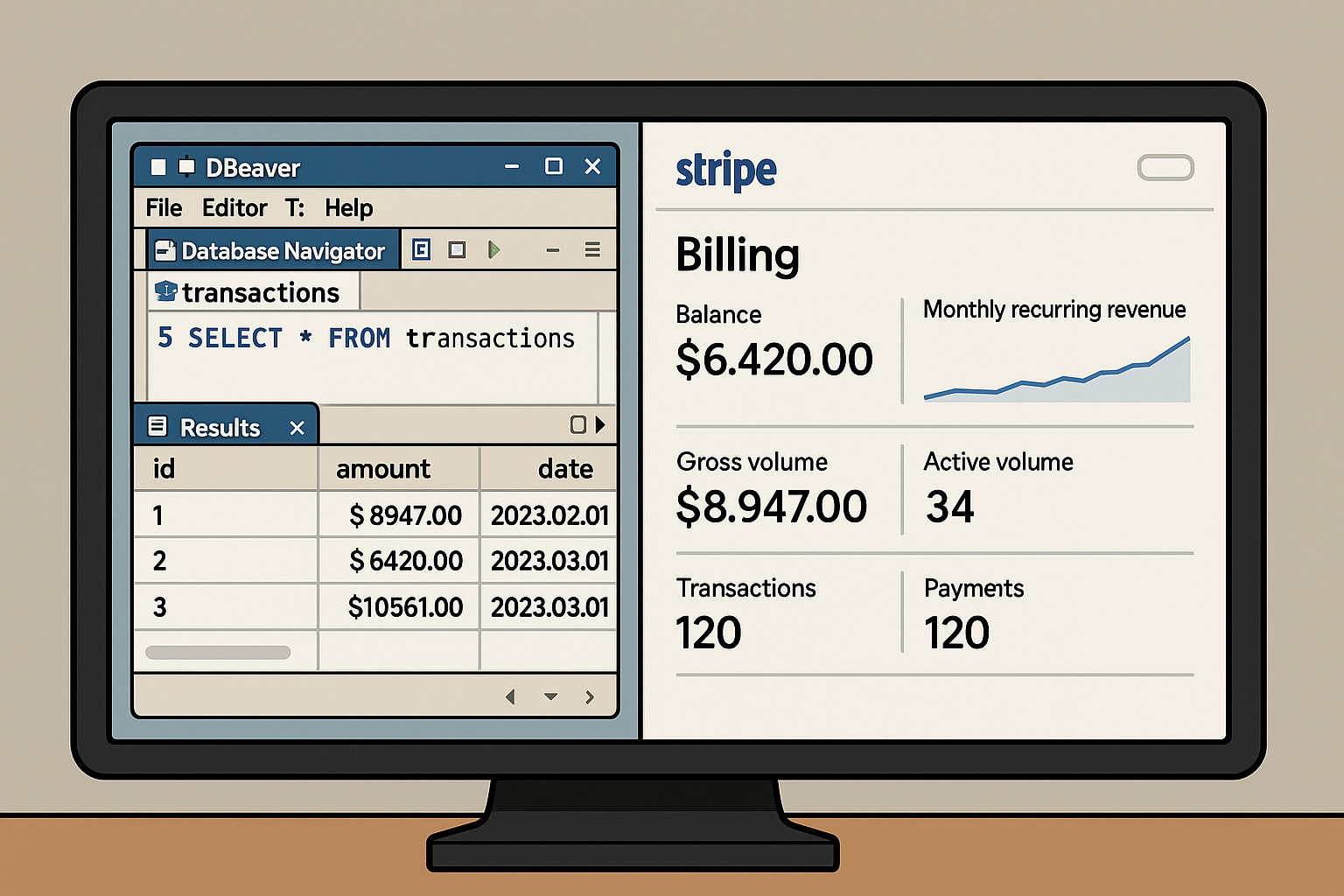

During the building phase, we live in an ecosystem of our own tooling: our database editor, our dashboard, our Jupyter notebook. This is what I call “the left hand of data”.

The left hand of data is not what our user sees. They see gross billings in Stripe, total delivered emails in Hubspot, or total contacts in Salesforce. They do not see, nor care for, the backend world we live in. The user lives in the frontend.

It is important for data practitioners to realize that, in some ways, the numbers we work with are “not real”. To us, data lives in a data store, such as MySQL or Redshift or parquet files in S3. We operate with the bare essentials: columns, rows and values.

In the backend world of databases and data stores, we do not see everything that frontend users see. The data is not formatted, not adequately labeled, not always relevant, and not contextualized within the broader business domain. In the backend, we lose the essential understanding for knowing whether a given calculation makes sense or not.

If a marketing analyst sees within Hubspot “812 emails opened last week”, the answer is 812. If we calculate COUNTD(CASE WHEN event_type = ‘open’ THEN event_id END) in our database and get 796, we are wrong. What is real to the user is what they see on their screen, not what we see in the database.

We could be wrong for many reasons - perhaps Hubspot applies custom email open logic, perhaps our ingestion jobs failed to bring in all the data, or perhaps we are simply using the wrong table - but one thing for certain is that a failure to reconcile means we are wrong.

Peering into the frontend #

Often, data practitioners do not have access to frontend tooling. They do not have access to the website or to Salesforce or to Google Analytics, and if they do, they do not have permission to view the data.

This means that data practitioners are foreclosed from knowing what the correct answer is.

How can we build data sets, dashboards, analyses and models if we do not even know whether the data is correct? We could be wildly off in record counts or totals and never know because we lack a frontend anchor against which to reconcile.

I often tell my team that “the left and right hands of data must meet”.

While we are naturally proficient in our own tooling, we also need to get into the frontend. We need to have the same permissions as the user and see the same things they are seeing. That is our source of truth.

When we meet with the user, they’ll often tell us what the numbers mean, what they’re not sure of, what the data lifecycle is, and what the business context is. It is here, in the frontend, that the once skeletal data comes to life.

Reconciling to the frontend is time-consuming. You need to log in, get the right permissions, explore the user interface, build reports, meet with the user, export data, compare differences to the backend, and document discrepancies. I remind my team that nearly a quarter to half of their development time will likely be spent on such “data QA”. Any less tells me we are flying blind.

The alternative of not performing data QA, however, is more costly. It occurs after you spend weeks building a data set or report or model, only to present to your stakeholder and have them object: “Your data looks wrong.” Data is only correct insofar as the left and right hands of data meet, and it is better to verify such correctness before a presentation than during one.

-

Why do I use “data correctness” instead of “data quality”? Data quality refers broadly to a set of properties about the data itself, which collectively make it “high quality data” or “low quality data”. Certainly one property of data is its correctness, but other properties include granularity, completeness, documentation and relevance. I use “data correctness” specifically to mean whether a given data set reconciles with other sources of truth. ↩