Perseveration and the economy of movement

A few years ago I came across a great word called “perseveration”.

Perseveration is a clinical term referring to a wide range of functionless behaviors, such as repetitive speech, action or thought, which persist long after the original situation has passed. More colloquially, we might think of it as “getting stuck” or “doing the same thing over and over again to no effect.”

Perseveration is not quite the same thing as dwelling on something, as you can dwell on something that is nonetheless useful. It is not quite obsessing over something - although obsessive compulsive disorder is certainly comorbid with perseveration - as obsession does not capture the repetitive nature of perseveration. Thrashing comes close, though its violent, desperate nature overstates the droning, useless banality of perseveration.

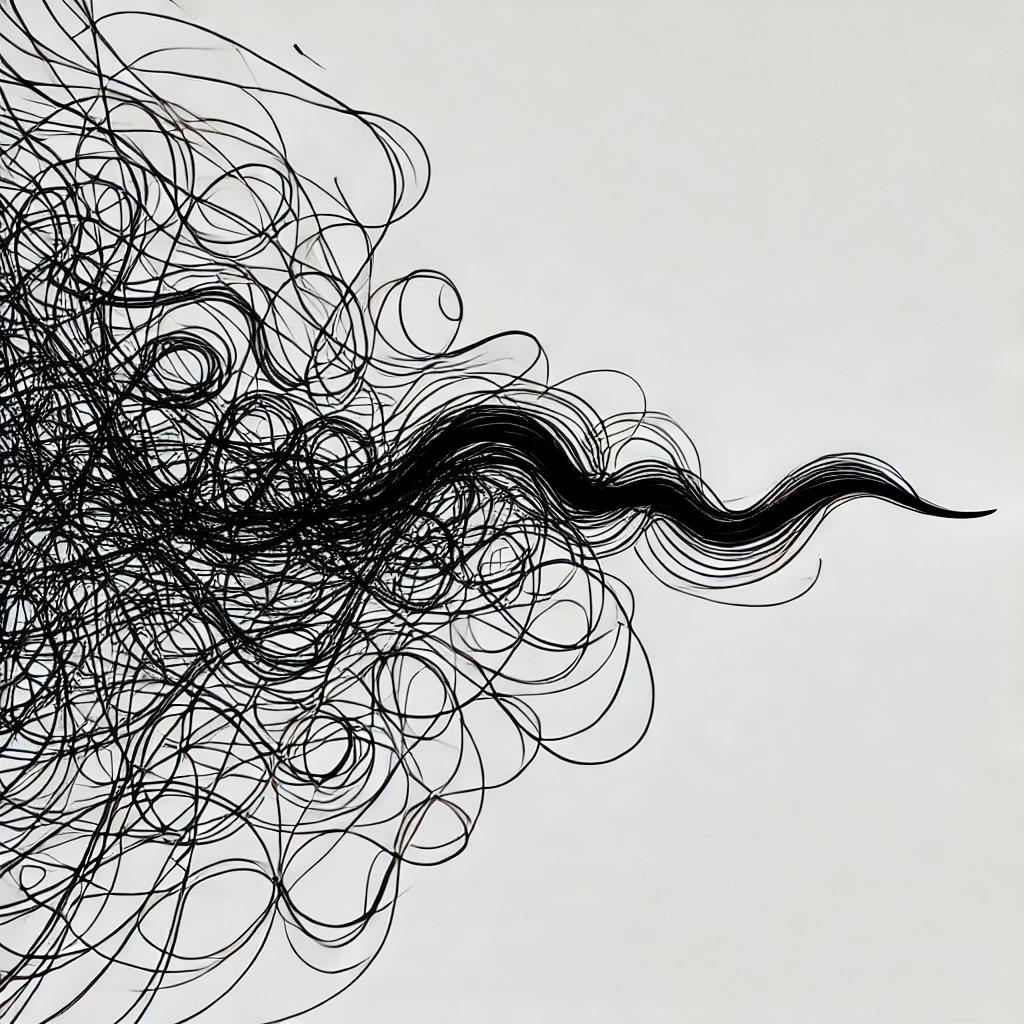

Back in 2018, having recently quit my job to move abroad and start a business, I was living in Poland. After about 6 months of trial and error, I ended up mostly with error. I soon jettisoned my original business idea and searched anew. I recall the feeling of grasping around for something - anything - that would rescue me from the abyss of failure. I thought and thought and thought. My mind spun like the tires of a car stuck in mud.

During this time I felt a compulsion to be busy - furiously scribbling down notes, ruminating before bed - because action appeared to signify forward motion. I didn’t realize that my incessant thinking and incessant doing crowded out a more sober, more reflective, and ultimately more productive mindset. I had become the dreaded “busy loop” of programming: a while-loop with no break condition. I was perseverating.

2 months later, I packed my bags and returned home.

Once I became aware of my own perseveration, I began to notice it in other places - especially at work. I noticed coworkers who wrapped themselves in a suit of meetings in order to feel busy and productive. I noticed peers who, anxious about an upcoming deadline, upbraided and belittled coworkers, fulfilling the old trope that “the beatings will continue until morale improves”. I noticed leaders who changed strategic direction so frequently their clockwise rotations landed them precisely where they started. Were these too all forms of perseveration?

On the nature of perseveration #

Perseveration appears to be an extreme case of otherwise completely routine, functional behavior. Throughout our lives, we exercise control over our environment in order to achieve our aims. We observe information from our environment, analyze it, form a decision, act, and ideally observe the outcome. These actions should, over time, bring us closer to our goals.

This “human control loop” is exceedingly simple. It is composed of:

- An action

- A result

- An inference that the action caused the result

If I pick up a glass of water and drink the water, after which I feel sated, then I will infer that my drinking of the water caused my satiety. If I drop a ball from the air, then observe it hit the floor, I will infer that my dropping of the ball caused the ball to reach the floor.

All 3 aspects - the action, the result and the inference - are necessary to have a complete feedback loop. If I don’t observe my own action, for example the ball magically appears on the floor, then I will not be able to infer that it was my action which caused the ball to be there. If I don’t observe the result - there is no ball on the floor - then my action of dropping it certainly did not place it there. Finally, the causal inference itself can be suspect: if I drop a ball from the air, and then at some point later I observe a ball on the floor, it is not necessarily the case that I caused the ball to be on the floor.

Perseveration occurs when this feedback loop is broken or unclear. If we are not self-aware of our own behavior, or if we are not observant enough of outcomes, or finally if we do not reflect on the causal relationship between our behaviors and the subsequent outcomes, then we will be stuck in a cycle of action which does not produce its intended effect.

Often, we are so focused on feeling busy, on speaking, on working, on doing, that we do not lift our eyes to observe the environment around us. Other times, we are so focused on other things and other people that we do not observe our own behavior. And even if we observe both our actions and subsequent outcomes, it takes a healthy dose of reflection to infer which of our actions are causing which of the outcomes we observe.

On the economy of movement #

From the outside, this type of reflection looks like a whole lot of nothing. Observing, inferring, thinking. But its plodding, methodical nature belies the immense power it wields. I refer to this as “the economy of movement”.

The economy of movement is the opposite of perseveration. It is the strategic deployment of energy only insofar as it produces desirable outcomes.

There is something deeply fundamental about the conservation of energy. Of course, it is the first law of thermodynamics. Given this physical law, it also manifests in biology as optimal foraging theory: organisms which do not allocate their energy productively are outcompeted by those which do.

The economy of movement looks like many things that we as a society regard highly. It looks like concision and parsimony, elegance and beauty, effortlessness and finesse, optimality and efficiency, or - my personal favorite - sprezzatura. Roger Federer playing tennis exemplifies the economy of movement.

The economy of movement does not reward blind action, as action without consideration of results may be wasteful. In the economy of movement, meditating on the relationship between cause and effect is just as important, if not more, than action itself.

The economy of movement looks like nothing instead of something. Less instead of more. Patience instead of impatience. Listening instead of speaking. It looks like the meticulous conservation of energy rather than the indulgent expenditure of it.

There is a time and place for action, and when it is necessary, it ought to be vigorous, effortful and intense. But action is not the only tool in our toolkit. Inaction is too. Because what appears to be inaction on the outside may instead be careful reflection on the inside.