Pace layers & the Hegelian dialectic

Hey all -

+ what I learned or rediscovered recently #

Pace layers #

In the back of my mind, I always wondered why government moves so slowly, or why it’s so hard to effect lasting change on peoples’ beliefs and traditions. Why doesn’t everything move as fast as business or technology?

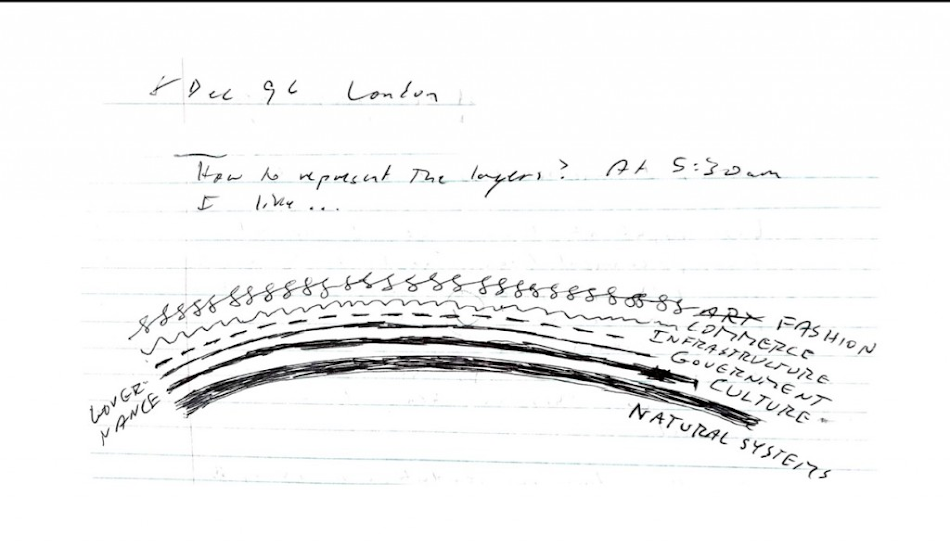

Stewart Brand of the Long Now Foundation reflected on the same thing back in 1996, and in a stroke of insight, scribbled this:

He called these the “pace layers”: different layers of society moving at different paces. At the top were very fast, constantly changing layers, like fashion and commerce. At the bottom, underpinning the whole system, were these slow-moving, powerful layers like nature and culture. In the middle were infrastructure and governance.

The top layers are where all the change and innovation happens, though not all of it sticks. Most change doesn’t make it down to the deeper layers, because the pace layers filter them out. If all of society changed at the speed of fashion and commerce, we’d be making mistakes all the time. Mistakes don’t really matter at the top layers, but messing with the climate or thousands of years of tradition on a whim can be much more destabilizing.

Sometimes, but not often, change actually comes from the bottom up. The bottom layers have all the torque, and when they change, they change violently. Think of shifts in the earth’s tectonic plates: we get earthquakes. Similarly in culture: mass movements, à la civil rights. In governance: coup d’état. And of course, these changes shake the foundations of the entire system, affecting all the top layers as well.

One place we can clearly see the pace layers in action are with startups. Startups always promise hockeystick growth, but inevitably realize S-curve growth. Growth starts exponentially but then tapers off as the startup achieves scale.

This is because startups start in the commerce layer, but as they grow, they are forced to work with the deeper layers. They get slowed down because now they have to interface more with governance or culture. You can see this today with Airbnb or Uber, for example.

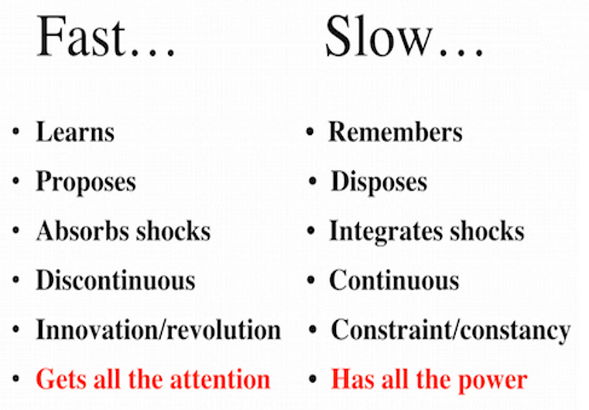

It’s good we don’t have all fast layers or slow layers. They have different strengths and weaknesses:

There’s really a lot in this mental framework so there’s really no way I capture most of it in a brief summary - I highly recommend watching the one-hour video.

Hegelian dialectic #

High-achievers have been taught implicitly or explicitly that achievement is everything: get good grades, go to a good college, get a good job, and so on. You could say the life thesis is: “achieve something.”

At the same time, we all know people who are the total opposite of this. Achievement is just some social construct. Who cares what other people think? Just follow your dream. Live on a farm, travel the world, pursue your passion. Pretty much the antithesis of high-achievers.

Considering both of these, we see a dichotomy - a binary choice. Black and white. It’s easier to compress complicated phenomena or systems - like how we should live - into two simple choices rather than the dozens of shades of grey in between.

I think, upon reflection, most people would reasonably admit that it’s not one or the other. You really should strive for some form of achievement in life - it seems like we’re built for it. At the same time, fixating on achievement at the exclusion of anything else which makes life worth living also seems misguided.

When we move beyond the binary, we arrive at synthesis: we begin with two opposing beliefs (thesis and antithesis) and arrive at a place of nuance.

It’s really impressive how much fits in this framework, also known as “thesis-antithesis-synthesis.” People love to see things in a dichotomy - either this or that - and once you use this framework, you see that those are just steps on the path toward synthesis.

It’s almost a methodological framework for how to think. If you have an opinion - or thesis - think of its antithesis. And if you have an antithesis, what is the synthesis? What elements from both stories can we use to further enhance our understanding?

What I love about this framework is it guards against being too opinionated and self-assured. If you’re really sure about your thinking on something, it’s now actually much more likely you’ve simply entrenched yourself in your beliefs, never considering the antithesis or synthesis.

+ parting thoughts #

In a previous newsletter, I wrote about how different spheres of exchange illustrate why people treat social exchanges so differently from market exchanges.

Here is a good summary by Chenmark Capital of some research supporting that.

Thanks for reading,

Alex