Extremizing algorithm, Metcalfe's law

Hey all -

+ what I learned or rediscovered recently #

Extremizing algorithm #

In one of my earlier newsletters, I suggested that you want to diversify your teams as much as possible, given a baseline of shared norms and values (e.g. civility, tolerance, free speech, etc.). My intuition was that we naturally select for people who are like us, and while this is generally good for relationships, it’s not as good for surfacing the best or most accurate ideas. So we have to fight the tendency to build ourselves echochambers.

The extremizing algorithm lends some credence to this notion.

Coined by researcher Philip Tetlock and popularized in his book Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, the extremizing algorithm says that if a lot of people with diverse backgrounds and opinions agree with you, you should actually increase your estimate of the likelihood of something being true.

In other words, if people with completely different experiences, data, biases and opinions also come to the same conclusion as you, then collectively you’ve covered a lot more of the hypothesis space. If you guessed a 70% chance of something occurring, and your diverse team also guessed around 70%, then you should all bump that up to 85% - that is, extremize your view.

Of course, you only get this benefit if you have diverse teams.

This sounds like an economic free lunch - better probability estimates from more diverse teams. But putting on my skeptic hat, I’d guess that teams which are too diverse are also slower to agree on a solution, less coordinated and more bureaucratic. Which would be a familiar tradeoff: accuracy versus speed.

This ties nicely into the next concept.

Metcalfe’s law #

One advantage large organizations have is that they benefit from economies of scale: as they do more and more of something, they generally get more efficient at it.

But there’s a flip-side to this: they also get diseconomies of scale (or less efficient) because they now have to manage and coordinate all these interdependent parts. In the words of Charlie Munger, “you get big, fat, dumb, unmotivated bureaucracies.”

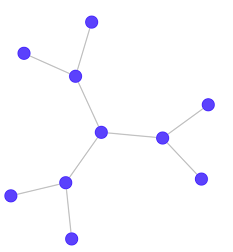

With a lot of interdependent parts, you have even more connections between those parts. For example, you may have an organization that looks like this[1]:

That’s five parts, but ten connections between the parts. If you have eight parts, then you can at most have twenty-eight connections.

This is Metcalfe’s law - or n * (n-1) / 2 - which is the number of unique pairings between parts in a network. It’s the upper-bound, worst-case scenario for the amount of communication between parts. But it’s indicative of complexity.

That image also looks strikingly familiar to a corporate boardroom: you have five people in a room, and everyone gets to voice their opinion, give an update on their work, get caught up to speed on everyone else’s work and get buy-in for new projects. Again: “big, fat, dumb, unmotivated bureaucracies.”

How do you mitigate this complexity?

Jeff Bezos proposed the “two-pizza rule”: never have a meeting where two pizzas can’t feed the entire group. Otherwise, your meeting is too big, too complex, too bureaucratic.

Instead, Bezos encourages small, nimble, independent and highly-coordinated teams. Everyone doesn’t have to communicate with everyone else in a single meeting - rather, they should work through “central nodes” which connect to other “central nodes.” Department head to department head[2].

And now we get something that looks like this:

Fewer connections between nodes, greater simplicity.

However, this too came at a price: we now get centralization of power. Good for getting things done, but notorious for introducing principal-agent problems. I think there’s a useful lesson here: if you’re not seeing tradeoffs (i.e. things are black-and-white), you’re probably not looking hard enough.

+ parting thoughts #

These are starting to get long again - I’ll try and be more concise next time.

Thanks for reading,

Alex

[1] Images come from this essay: http://alexkudlick.com/blog/what-the-four-color-theorem-can-teach-us-about-writing-software/

[2] To take a recent example in software, you can see this in the recent “microservices” trend. Every service should be autonomous, independent and have clearly specified, “contractual” ways in it communicates with other services (i.e. its API). You can’t interact with the service without going through these clearly defined channels. And while this may take longer to structure, it helps to reduce complexity.